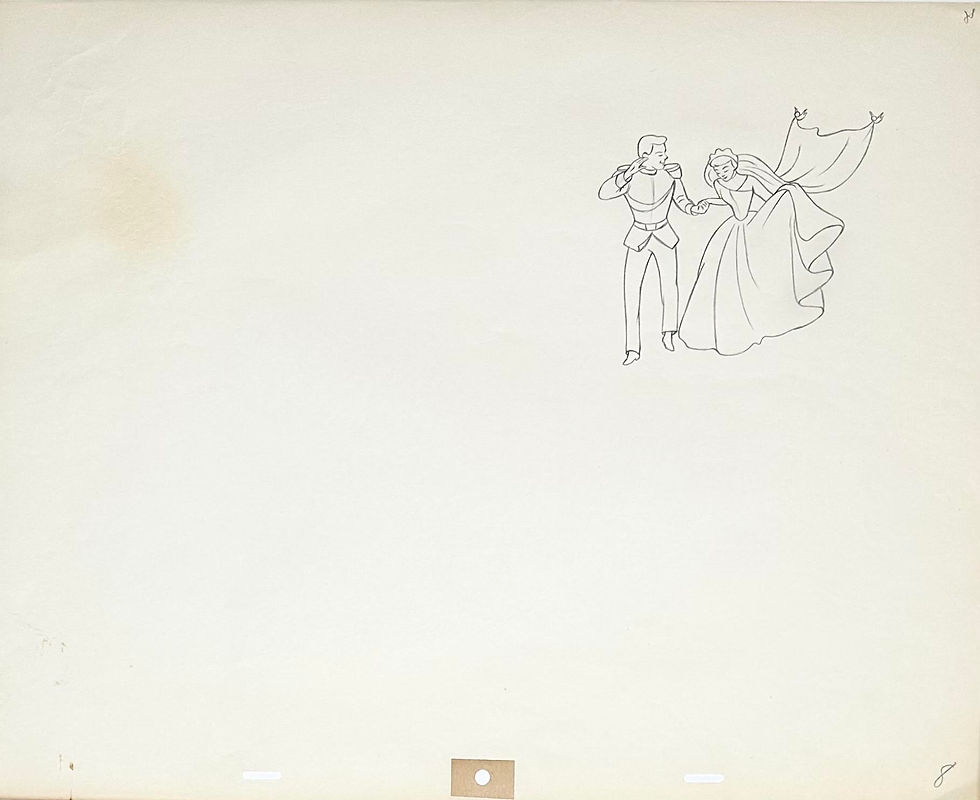

Original Production Animation Drawing of Cinderella and Prince Charming From "Cinderella," 1950

- Untitled Art Gallery

- Jan 13

- 5 min read

Original production animation drawing of Cinderella, Prince Charming, and Two Birds in graphite pencil from "Cinderella," 1950, Walt Disney Studios; Numbered 8 in pencil lower right; Size - Cinderella, Prince Charming, & Two Birds: 4 1/4 x 4 1/4", Sheet 12 1/2 x 15 1/2"; Unframed.

The 1950 Walt Disney feature film Cinderella was based on the French version of the fairy tale written by Charles Perrault in 1698. Released during a crucial rebuilding period for the studio, the film became Disney’s second great Princess feature, following the groundbreaking success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Over time, Cinderella has come to occupy a central position in the pantheon of Disney Princesses—perhaps because she stands apart from the others as the only Princess who does not begin her story with noble blood, yet ultimately ascends to royalty through kindness, perseverance, and inner grace rather than lineage.

Cinderella herself was animated primarily by Marc Davis and Eric Larson, two of Disney’s legendary “Nine Old Men,” each of whom approached the character from a distinct artistic perspective. Davis emphasized elegance, refinement, and classic beauty, while Larson favored a simpler, more approachable demeanor. Rather than conflicting, these contrasting interpretations complemented one another, resulting in a heroine of greater emotional depth and complexity than her predecessor, Snow White. As with many Disney features of the era, live-action reference was employed to ensure believable human movement. Actress Helene Stanley performed the live-action reference for Cinderella, later returning to the studio to model for Princess Aurora in Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Anita Radcliffe in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961).

Christopher Finch, in his seminal book The Art of Walt Disney, describes the studio’s reliance on live-action reference during this period:

“Disney insisted that all scenes involving human characters should be shot first in live-action to determine that they would work before the expensive business of animation was permitted to start. The animators did not like this way of working, feeling it detracted from their ability to create character. The animators understood the necessity for this approach and in retrospect acknowledged that Disney had handled things with considerable subtlety.”

The casting of Cinderella’s voice was equally meticulous. Approximately 400 women and girls auditioned for the role, but it ultimately went to Ilene Woods. At the time, Woods was working in radio and was unaware she was even being considered. Friends and colleagues Mack David and Jerry Livingston asked her to sing a song from Cinderella and secretly submitted the recording to Disney Studios. Upon hearing it, Walt Disney immediately recognized the perfect voice for both the spoken and sung character and personally reached out to Woods, securing one of the most iconic vocal performances in animation history.

Prince Charming was animated by Eric Larson, who later admitted—according to animator Andreas Deja—that he felt some embarrassment over what he perceived as stiffness in the Prince’s performance. Despite this self-criticism, the character became a template for Disney Princes for decades to follow. Prince Charming was voiced by William Phipps, whose audition so impressed the studio that Walt Disney himself offered him the role. Phipps enjoyed a prolific career in classic science fiction films and westerns across both cinema and television. Interestingly, while Phipps provided the speaking voice, the singing voice for Prince Charming—most notably in the duet “So This Is Love”—was supplied by Mike Douglas, later famed as the host of The Mike Douglas Show.

A lesser-known piece of trivia is that the Prince’s name is never revealed within the film itself, nor is he ever referred to as “Prince Charming.” That designation appeared later in merchandise and subsequent adaptations. Historically, Prince Charming holds several distinctions: he was the first Disney Prince to perform a duet with his love interest, the first to be featured in an on-screen wedding celebration, and the first to dance with his heroine immediately after meeting her.

The wedding scene at the conclusion of Disney’s Cinderella (1950) is brief, almost understated, yet it carries significant emotional and thematic weight. Rather than functioning as a lavish spectacle, the scene serves as a visual and narrative resolution to Cinderella’s journey, emphasizing fulfillment, justice, and transformation.

Visually, the wedding is presented as a storybook image brought to life. The setting—a grand castle bathed in light, with flags waving and bells ringing—recalls the opening of the film, which begins with a fairy-tale book. This circular structure reinforces the sense that Cinderella’s story has reached its destined ending. The animation favors clarity and elegance over excess: Cinderella’s gown is refined rather than ostentatious, and the color palette is soft and luminous, underscoring purity, hope, and calm after conflict.

Narratively, the wedding scene confirms Cinderella’s identity and worth. By the time the audience reaches this moment, the tension surrounding the glass slipper and her recognition as the Prince’s chosen bride has already been resolved. The wedding does not introduce new drama; instead, it affirms that Cinderella’s inner virtues—kindness, patience, and resilience—have been rewarded. Importantly, the film avoids portraying the marriage as a sudden reward alone; it is framed as the natural conclusion of a bond already established at the ball.

The scene also functions as moral closure. The absence of the stepmother and stepsisters from the wedding imagery subtly reinforces the film’s ethical framework: cruelty and envy are excluded from the final harmony. Meanwhile, the presence of familiar supporting characters—such as the mice—adds warmth and continuity, reminding viewers of the personal relationships that sustained Cinderella before her transformation.

From a broader Disney perspective, the wedding scene exemplifies the studio’s early approach to romance and fairy-tale endings. It is idealized and symbolic rather than realistic, prioritizing emotional satisfaction over detail. The emphasis is not on the institution of marriage itself, but on the promise of happiness and belonging after hardship. As such, the wedding operates less as a social ceremony and more as a visual metaphor for Cinderella’s complete liberation—from servitude, isolation, and despair—into a life of dignity and joy. In its simplicity, the wedding scene encapsulates the film’s central message: dreams, when paired with goodness and perseverance, can come true.

This is a rare and wonderful drawing of Cinderella and Prince Charming from "Cinderella," 1950 which occurs in the climatic wedding scene at the end of the film. Cinderella is wearing her wedding gown and her veil is being carried behind her by a pair of flying birds; as she is holding hands with Prince Charming descended the stairs of the castle after being wed. A fantastic piece of vintage Disney artwork that is perfect for any animation collection!

#Cinderella #WaltDisney #Disney #productiondrawing #cel #animation #animationdrawing #EricLarson #MarcDavis #IleneWoods #LesClark #Jaq #Gus #Lucifer #Stepmother #LadyTremaine #animationart #untitledartgallery #animationcel #ChristopherFinch #CharlesPerrault #Anastasia #Drizella #Prince #PrinceCharming #MikeDouglas #WilliamPhipps